Sri Lanka: A Sharp Bounce Back from the Pandemic

Thanks to the local government, fully vaccinated travellers can now experience the splendour and hospitable culture of Sri Lanka once again with no quarantine restrictions.

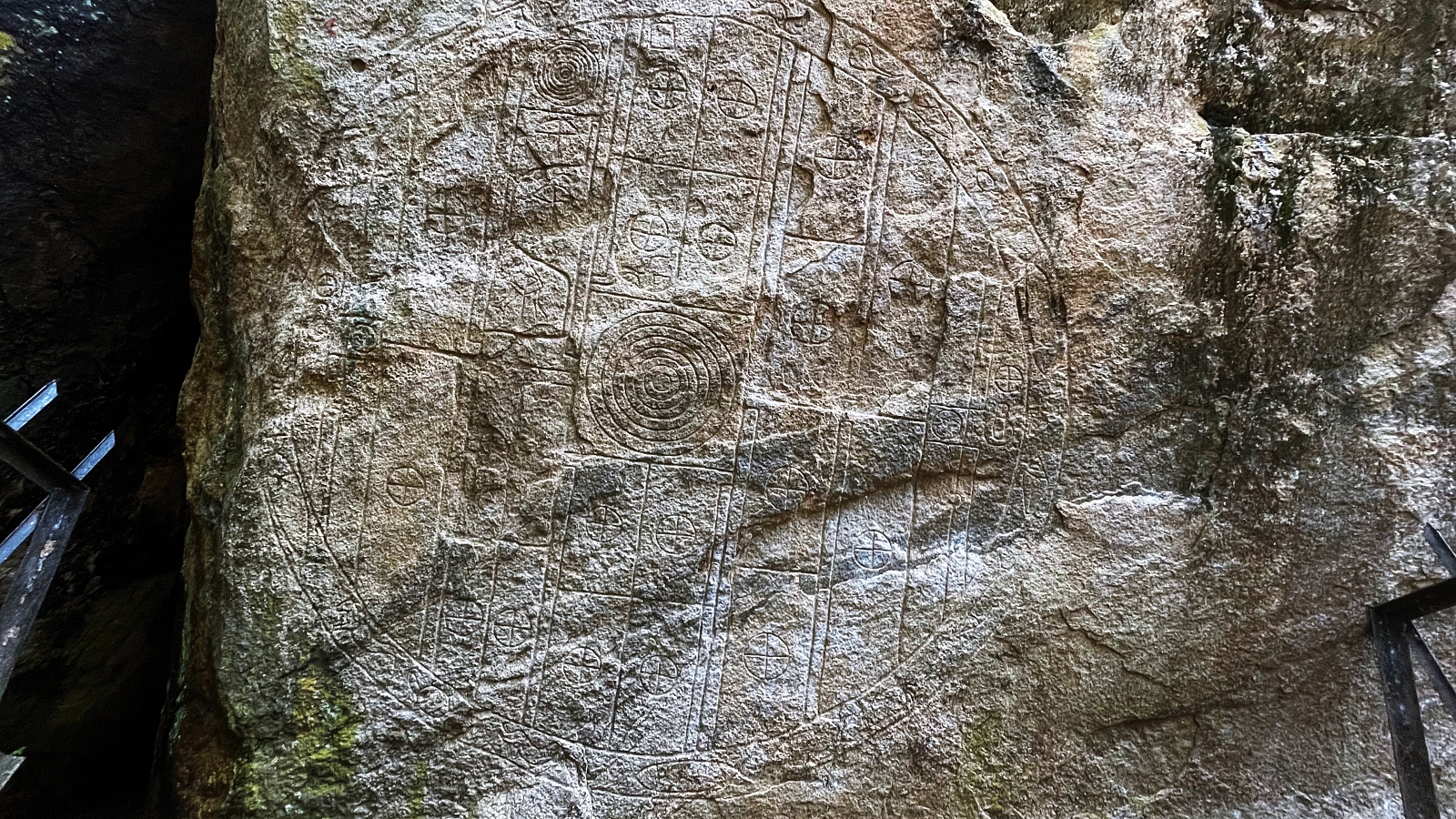

From taking a look at South Asia’s tallest tower from its rooftop terrace in Colombo to tasting the world’s spiciest dishes in Jaffna, a recent trip to Sri Lanka showed me how the island is bouncing back sharply to revive your lust for travel. Whether it’s 1st-century temples in the Northern province or a stargate portal in the central, every person’s experience takes on a different form of adventure in Sri Lanka. Beyond amazing sights or food, the country harbours its cultures and preserves its hospitality, making it easier to communicate with the locals.

Of course, the country is significantly reliant on tourism, largely nearest neighbours, its rapidly growing tourist markets. Sri Lanka reopened its borders in September 2021, and there are no quarantine restrictions for fully vaccinated tourists. The government has rolled out an efficient and meticulous bio-bubble model to protect tourists from Covid-19, establishing an example for the rest of the Indochinese Peninsula. Bio-bubbles are safe and sanitised environments where you coexist with other vaccinated individuals.

With this new bio travel bubble initiative, Sri Lanka has opened up new possibilities for international travel. The protective bubble sees to it that landing tourists come in contact with vaccinated ground staff. Gets even safer when you book your stay with an accredited Level I hotel where sanitisation is the premium priority. A month after the launch of the travel bubble, I decided to visit Sri Lanka and take a venturesome vacation across not one but four of its different provinces. I was greeted with warmth wherever I went; it stems from deep inside the island culture.

If anything, the pandemic has only strengthened the strong sense of community everywhere. I felt it the minute I set my foot at the Colombo airport. It was past 10 pm. The airport staff quickly scanned my negative RT-PCR report and QR code from the online declaration form. Those that didn’t submit it online were handed a printed version. Even though Sri Lanka offers visa-on-arrival to most countries, it’s advisable to be in receipt of an e-visa. It ensures a hassle-free transition. With my handy passport and documents, Immigration took less than ten minutes.

A silver cab by an accredited tour operator drove me from the airport to Movenpick, a level one hotel in Colombo. Siri (as his name is) is a fully vaccinated driver and my cicerone for the next two weeks. Rather stout, with a kind demeanour, Siri was usually veiled behind a mask, with only his big eyes visible. The one hour night drive threw in a different perspective to the city. Colombo roads, slick as ever, beam with distinguishable details and a sprawling network of lights all the way to the inward coastlines. The radioactive markers on the expanding ring roads help you trace trade routes, dark expanses, and the orderly grid of the city.

Following the comfortable suite stay and Asian food indulgences at Movenpick, I went sightseeing around the most bustling city of Sri Lanka. The new bio-bubble initiative enabled me to move freely within safe zones. I rambled my way across Colombo’s wide streets for the next few hours, basking under the October sun. I lay my gaze upon the mounting pyramid of Buddha statues at Gangaramya temple and my heart on the sweet candy-striped Jami-Ul-Alfar mosque in the Pettah market. My mortal frame spurred with thoughts as I stood feeding the sacred flame.

Midway on the ground, beside the Colombo Lighthouse I, leaned against the armed man. Then I ascended the tallest tower in South Asia to see the lotus up close and let the melancholy of the independence hall win my embrace in exchange for a stall. It was reassuring to see celibate Buddhist monks everywhere, only this time, equally gratifying to see people veiled behind their safety masks. The day came to a close with a generous serving of grilled meats and the lingering light of Colombo’s night sky listening to my harp. And I slept off the soft and doleful air of an old nostalgia.

Blame it on the continuing uncertainty of the pandemic; the plan to take an air taxi to Jaffna was thwarted, by a provincial lockdown. Dealt with the grim crisis by hitting the road instead! I may have made the best decision because Colombo to Jaffna was an outlook update! The onward trip of nearly ten hours allowed me to map the contrasting socio-cultural values of the overcrowded and the less crowded towns.

This calm October morning had entirely yielded to the sun, exposing natural assets to perfect sunlight. As we propelled across a narrow causeway interposed with winding slopes, my vacant mood caved into lotus seeds tossed ashore the preceding lakes, rice paddies skimmed to the surface of the low-lying marshlands, and Indian heritage halting like an invisible breeze. The moving soul of the sportive wanderings had its wings, its horse, and its chariot.

Soul-sitting by the shores of an old affair, Jaffna is an unheard noise of Tamil intellectuals. Delighted much to listen to those sounds, I progressed along the furrowed coast when unexpectedly, through a thin awning of a sparkling haze, appeared a protruding land attired in a leafy glade. The blissful idleness of that sweet forenoon with all its exquisite visions changed to a Portuguese musing. Its name translates to the port of the lyre and its spirit to a Tamilian pyre. The damage may have been unprecedented in its sweep, but Jaffna seems to be rebounding beautifully after ending the thirty years of war.

Anyone considering a vacation during the pandemic NOW is the best time to visit Jaffna. Swim on beaches, go angling, bask in the winter sun, trek up temple trails in villages, or sail on the ocean waters – Jaffna lets you engage in all leisure activities with the new bio-bubble initiative. And it’s quiet and uncrowded like some of the other touristy places. I played with my time and wandered around this quaint little town, dubbed as the intellectual centre of the Tamil world. Men in Dhotis, women in colourful sarees. It felt like India. I uncovered a modest library, a crumbling fort, an old clock tower and a verdant grape vineyard within the city bounds.

Jaffna grape farm is unique to the region, the library was once Asia’s-largest, and the fort looks like a star from above the clouds. In the outer region, Nainativu, on the island’s northernmost tip, piqued my interest with its rituals, handed down over generations. Both the Shakti Peetha of Nagapooshani Amman Temple and the Buddhist shrine of Nagadeepa Purana Viharaya are here. A brief chat with the local priests reveals cultural similitudes, a spirit, they say, gets more robust in the course of religious festivities. Tamil Newyear, Deepawali, Thaipongal, and Nallur Temple festivals are the island’s main.

But I also went beyond temples and tried many other exciting activities in Jaffna. I ate lunch at Thinnai Organic, an agritourism hotel serving organic meals; shopped at markets beaming with sustainable handicrafts; walked amused across the art-decorated streets; and unwinded to Arrack, an everyday pour, with a mid-palate sweetness that finishes in poignant, fruity tannins. Easy to drink on the rocks or with juice for a midday tipple.

The Palmyrah arrack business in Jaffna has drastically altered Sri Lanka’s global market in recent years. Before the government started exporting, the problem was not making more Arrack, the problem was selling it. Back then, the toddy and the arrack societies had put a limit on the amount of ‘Toddy,’ tappers could bring in a day. The number was restricted to 30 litres a day, so the tappers were poor. With the emergence of global exports – Tappers can bring as much as they can. That empowers them to increase their revenue to ten times the former income.

I gained a better understanding of the topic as I got chatting with Suganthan Shanmuganathan and Jekhan Aruliah. Shanmuganathan is the leading distributor of Toddy and Palmyrah products in Sri Lanka and Canada, and Aruliah, a journalist. “He changed the labels. He changed the packaging. He improved the quality of Arrack to make it more consistent. Now he exports the Arrack and Toddy all around the world,” says Aruliah. According to government records, palmyra is plentiful in the north, with roughly 11 million trees in the region.

While wartime wreckage and shelling transformed the terrain, trees that survived, remain. “After Suganthan Shanmuganathan stepped in to tap the economic potential of this abundant natural resource, nearly 4,000 people now work as toddy tappers to strengthen the sector.” So the tappers who made 18000 a month earlier now make 1,80,000 on an average. After spending 25 years in Canada, Shanmuganathan, who returned to Jaffna in 2014, says, “My immediate motivation to return was for my children to be in touch with their roots.

Then I discovered the difficulties faced by the families of tappers. I hoped to positively change the living standards of toddy tappers while boosting this insignificant society. I looked at the existent process and gave my suggestions based on my expertise of the manufacturing process I had learned in Canada.” Everything, however, is owned by the cooperatives, including the manufacturing. With palmyra professionals banding together to improve the quality, palmyra products are all export-ready. What started with one product is now wholesale of 80 in range. From jaggery to Odiyal and from tuber flour to palm jam, Palmyrah sees no stopping in the modern world.

Buffalo curd with Palmyra palm treacle is one of the best desserts Sri Lanka offers, but you can’t leave Jaffna without trying the Ice cream at the Rios. My personal favourite – Coffee and chocolate sundae nuts priced at LKR 300. A detour to the North Central Province ushered me to Anuradhapura, a city rooming in its sculptures. After two days of beholding the city, I seek it as a blessing thereof. The inhabitants of this sacred city marvel extensively at worshipping the Buddha. So they took me to the stupas and temples amid Anuradhapura.

The monasteries are dotted with wilted statuaries; the venerated shrines recite time-honoured commandments; the divine hymns put you in a soul-sanctifying trance, and the iconic festivals amp the sacredness of the city where Buddhism is a way of life. Today, what remains is the collective memory of Anuradhapura under the Buddhism inclined Sinhalese kings.

Plagued by invasions, rescued by faith, Anuradhapura is a pastoral poem written by Buddhists. Take a cue from history, and you will discover that King Pandukabhaya was the glory of this beautiful kingdom. He established Anuradhapura as his capital in 377 BC and turned it into a prosperous municipality. Anuradhapura, however, gets its name after the minister who founded the settlement. The world heritage city elaborates on material and spiritual understandings.

Anuradhapura, the ancient capital of Sri Lanka, reflects the urgency felt to protect sacred spaces. The sermons of Sri Maha Bodhi, the massiveness of Ruwanweli Maha Seya, Jetavanaramaya, and Abhayagiri Stupa, and remoteness of Isurumuniya Rajamaha Viharaya, Ranmasu Uyana, Lovamahapaya and Brazen Palace will leave you astonished. Visit these sites to become heir to ancient stories alighting to Heaven, and collect wishes fared out in the temple bell ringers. I had my share of traditional lotus leaf meal at Ambula and another in a fine dining atmosphere at Habarana Village.

Fried river fish, Gotukola Sambal, pumpkin curry, Manioc leaves Thibbatu Mallum, and a variety of Polos were the standout dishes. The curries are served with red rice. I came to something rather unusual, farther up the central province – the sweeping quiet. Kandy and Nuwara Eliya, on highland, are natural access to the remote inventory. Much of the day, in these cities, is a great deal of mist, but by midday, the breeze calms down and silence returns. Day chimes like a peaceful dark! Most houses are guarded, with metal railings, walkways, heavy doors and green colonial rooftops.

I stayed in Blackpool resort at the foot of Meepilimana Forest Reserve, in a lush, decorous valley with dramatic tea plantations ahead and behind us. Occasionally, a few drones flew overhead, but a faraway car never made as much noise. As the woods unfurl a dream, as the eternal hills gleam, the rising peaks attract all attention and make everyone’s heart skip a beat. The temple street in Kandy and the city market in Nuwaraeliya are busy thoroughfares with bus routes and coffee shops. However, with the epidemic on the horizon, the city no longer has the same ring to it!

The idle chatter and other frequent resonations have faded in the gentle murmurs of birds. And that realization is as startling as the sight of deserted streets. But living here is a haven so timeless, a taste of nature so fascinating. Come to embrace the mist-clad hills, nature’s mightiest riches and exquisite sightings of sprawling tea estates. In the Western province, the noise of cars no longer drown out the rustle of the Negombo wind. Because the west coast city of Negombo is only fifteen minutes away from the international airport, it was my last stop in Sri Lanka.

Known for its sandy beaches, cinnamon plantations, and centuries-old fishing industry, Negombo is a Roman catholic predominance once ruled by the Jaffna kings. They built fortifications at Negombo. In the 16th century, Portuguese colonists landed. Descendants of those who worked for Arabic ships on the Negombo port are known as the Moors. The 16th-century Negombo fort, and other Nederlandse structures, churches bear clear witness to the Dutch colonial era.

The semi-enclosed coastal basin of Negombo Lagoon is connected to the Indian Ocean and supplied by the Dutch canal. But the mangroves surrounding it offer better opportunities at spotting aquatic birds and local forestry. As for the village life, the fishermen live in shacks made of thatch palms and make a living through outrigger canoes and nylon nets.

Oruvas (sailing canoe) and Paruvas (rowing canoe) are the two types of boats they make. The fishermen in this region have also improved their income by collecting palm sap to make arrack. I’d say visit Negombo to find inspiration in nature and let the duality of the ocean intrigue you with its tidal thoughts. This city shows you why there is no need to curtail your wanderlust if you can work in a safe environment by a quiet beachside.

Let leisure time catch on as your work moves to the beach. I explored this option with Heritance Negombo and turned to Jetwing Blue for my Ayurvedic needs. Both massage and lunch. Visit this port city to play with mud and clay on a bright blue day, and let the sun warm you up like the fresh summer haze. Return feeling rejuvenated! Isn’t that what we all need today to beat the blues of the pandemic?