Partition Museum – Recalling a watershed moment in world history

Once a British Headquarters and prison, Partition Museum is now alive with 1947 tales of undivided and divided India that will leave you speechless.

As I strolled past the Town Hall, a wave of nostalgia for the colonial buildings from the 1800s washed over me. The exteriors radiate a warm, peachy hue, and are decorated with larger-than-life portraits of those whose lives were forever altered by the Partition. By preserving these legacies in the colonial building of Amritsar, a mere hour away from Lahore, a city that itself has endured much division, the Partition Museum stands as a poignant tribute to the survivors of such a tumultuous period.

A ‘No Photography’ sign, like a sentry, stands guard at the museum entrance. I ventured down a winding passageway and soon arrived at a dimly lit room which marked the entrance to the world’s first Partition Museum. Divided into 14 galleries, each featuring a different chronological theme – from ‘Why Amritsar?’ to ‘Hope’ – I was ready to explore the dramatic scenes of resistance (1900-1929), the rise (1930-1945), and the prelude to independence, partition, migration and refuge.

Table of Contents

‘Why Amritsar’ and ‘Punjab’

The first two galleries – ‘Why Amritsar?’ and ‘Punjab’ provide an insight into the local communities and a broader national chronicle. The passionate notes of freedom songs wafted through the air, as I walked through the 1st Gallery, while my guide Prabh waxed lyrical about why Amritsar was the perfect locale to host the Partition Museum. He informed me that this was the last station for those going from India to Pakistan and the first one for those travelling from Pakistan to India.

Prabh then gestured towards an old photograph of the golden temple and asked me if I could spot something that didn’t belong. I racked my brain until he eventually divulged that – that wherever the British went, they always left their mark – in this case, it was a clock tower they built in 1920 that was demolished by the people of Amritsar after independence. Prabh also regaled me with stories of how the statue of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Amritsar had replaced the statue of Queen Victoria that once stood in the same place.

The 1st Gallery sets the tone with the picture of the 1947 Hall Bazaar shopping street, scorched by fire. The Urdu captions are a nod to Amritsar’s long-standing Muslim identity. There are also 17 textile labels from the era of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, an 1888 map which highlights Amritsar as a ‘holy walled fortress’, as well as handmade phulkari and bagh prints that stimulate memories of Katra Ahluwalia as the former trading hub. The 2nd Gallery presents artefacts from the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh – a 100-year-old brass Hamam (geyser), a 1931 map predating the partition of India, and a certificate for permission to sit in the presence of a British official suggestive of the many indignities endured by Indians during the Raj.

‘The Resistance’ and ‘The Rise’

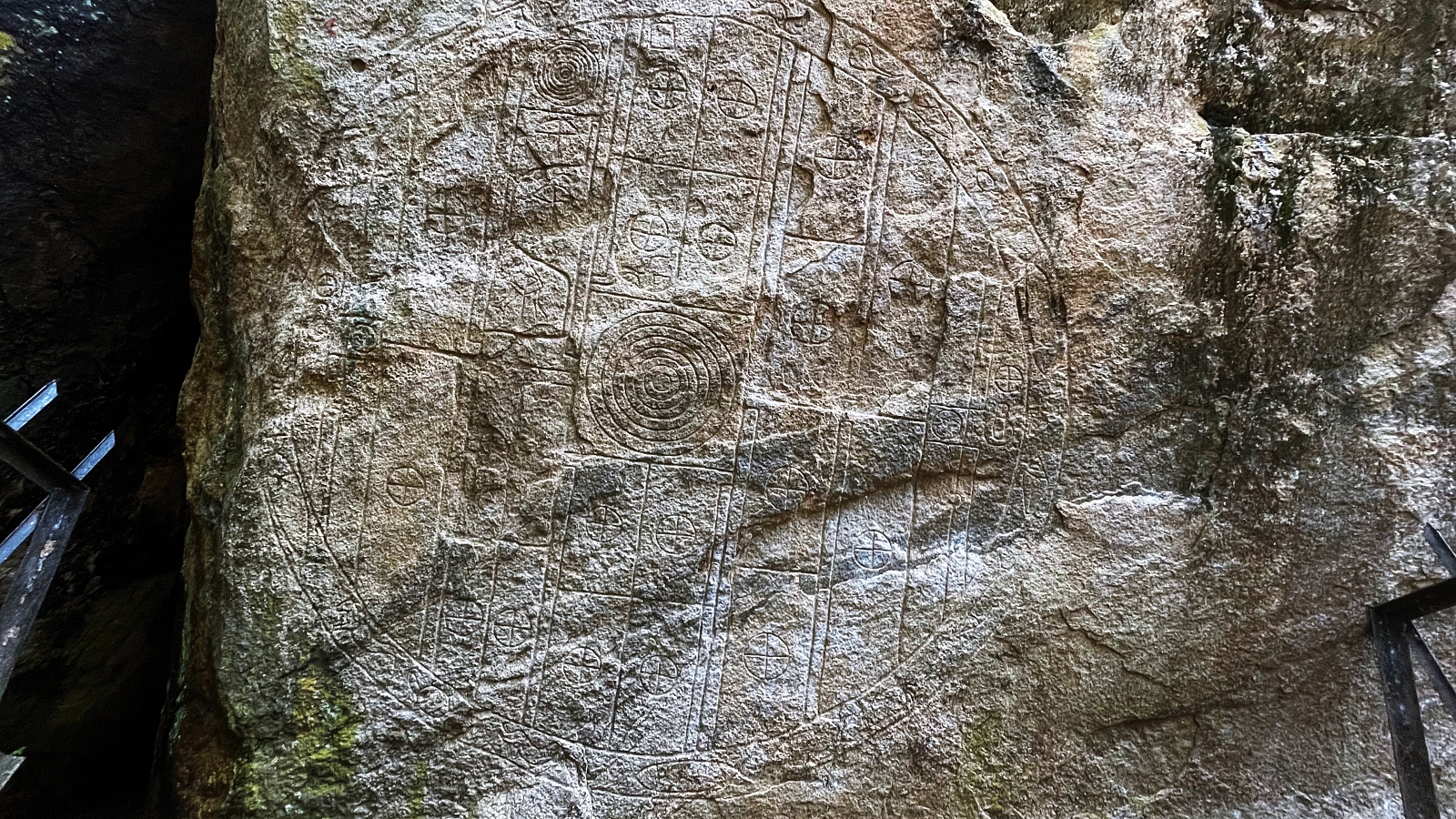

The third ‘The Resistance’ and fourth ‘The Rise’ galleries probe the anti-colonial movement and offer an immersive experience with jail installations between 1900 – 1931. The highlight of this revolutionary Gallery for me was the original board of “Simon go back,” the Young India weekly journal by Mahatma Gandhi that inspired 18 billion people to join forces in the fight against the British, and the pamphlets from the aftermath of the 1905 partition of the Bay of Bengal that cry out “Wake up, wake up! The day of the festival of force has come!”

A 1919 photo of the Jallianwala Bagh, a glimpse of the Komagata Maru incident, the division of Bengal on 16th October 1905, the formation of the All India Muslim League in 1906, and the inception of the first Indian National Congress in 1885 are all present. But my grief intensifies when Tagore’s “O amar sonar Bangla, ami tomai bhalobashi” – the 1905 protest anthem of Bangladesh – plays in the background, accentuating the insensitive ‘Divide and Rule’ reforms from 1909, and the growing resistance to the British and the Roulette Movement.

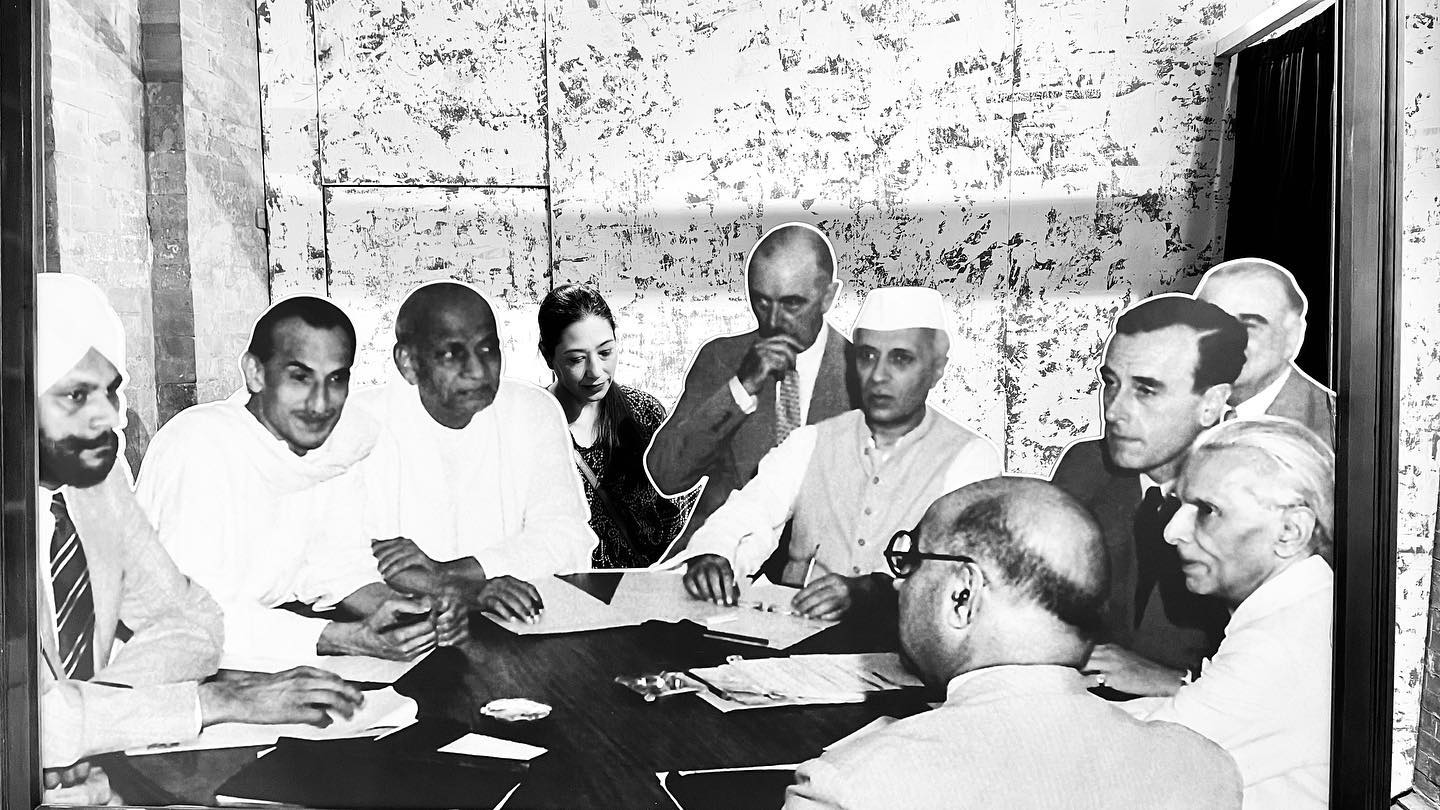

Political and Geographical Turbulence

As I march beyond the 1930s; Galleries 5, 6, and 7 take me into the political and geographical turbulence of British India’s final days. These galleries are the most interactive, with installations such as bullet-riddled crumbling walls, bringing the tales of those impacted by these cataclysmic events to life in an unforgettable way. They hold the beguiling narrative of Radcliffe’s life with a resplendent exhibit of his feats to his service in World War II. The display paints a picture that, while Radcliffe may have drawn a line of abysmal consequences that brought untold suffering, he was merely dealing with a dreadful job. Folded away in the depths of Gallery Seven lies an enthralling tale of resilience and recuperation for women.

The Great Exodus of 1945

The eighth Gallery connects the past and present, picturing independence, partition, and the great exodus of 1945. Strolling through the 9th and 10th exhibits of the Partition Museum, a sense of tragedy is almost palpable, and nowhere more so than in the poignant Well installation, a tribute to the countless women who, in the violence of Partition, chose to take their own lives rather than face the harrowing gendered violence of abduction and abuse. As I ascended the stairs in Gallery Ten, I was rewarded with the ‘Refuge’ of Gallery eleven through thirteen. Here, you will find the exhibits of the individual stories of the displaced the possessions they took with them and even their descendants.

Hall of Hope

At the very end of my visit, I finally encountered rays of hope in the last Gallery. Paper hangings of migratory birds directed me to the Hall of Hope, where designer Neeraj Sahai has crafted a splendid ‘Tree of Hope’ out of barbed wire. This installation provides a reflective space for visitors to contemplate the implications of Partition and the museum, and the chance to contribute to the tree, turning it greener. With each passing day, the ‘Tree of Hope’ becomes increasingly green with messages of peace, love and hope, as visitors leave behind stories and experiences, often passed down through generations. I left the museum feeling overwhelmed with a bittersweet pang of nostalgia and inspiration.

Partition Museum is an inspiring illustration, delving deep into the intricacies of the Partition and the colonial state. However, what truly sets it apart is its seamless linkage to the cityscape of Amritsar; providing a window into the everyday lives of Punjabis and Indians amidst this momentous historical episode.