Geghard Monastery: Beyond the Stone Walls

Amidst the dramatic landscapes of Armenia, nestled amidst the soaring cliffs of the Azat River Gorge, lies the otherworldly Geghard Monastery. This UNESCO World Heritage Site is a testament to the ingenuity of Armenian medieval architects, who carved a breathtaking sanctuary into the very heart of the mountain. As you approach the monastery, its sheer scale and intricate details captivate the senses. The monastery complex comprises a series of churches, chapels, and tombs, all meticulously carved into the rockface, blending seamlessly with the natural surroundings. Sheltered by towering cliffs on its northern flank, the Geghard Monastery stands as a testament to Armenia’s rich architectural heritage.

Just before the main entrance, a series of shallow shelves in the cliff face beckons visitors to test their aim and their dreams, for it is said that a pebble successfully lodged upon these rocky ledges heralds the fulfilment of one’s deepest wishes. Stepping through the fortified gateway, one is immediately ushered into the heart of the complex, where 12th-13th century ramparts stand guard, protecting three sides of the sanctuary, while the sheer cliffs provide an impenetrable barrier on the fourth. A leisurely stroll across the compound leads to the secondary entrance on the eastern side, where a table dedicated to ritual animal offerings (matagh) stands sentinel, and a bridge gracefully spans the nearby stream.

Encircled by a protective wall, the monastery’s sacred structures span from the 4th to the 13th centuries. In its earliest incarnation, the monastery bore the name Ayrivank, meaning “Monastery in the Cave,” a reflection of its unique rock-cut origins. Its foundation is attributed to St. Gregory the Illuminator, a pivotal figure in Armenia’s embrace of Christianity, a decision that would shape the nation’s cultural landscape for centuries to come. The name Geghardavank, which literally translates to “the Monastery of the Spear,” is deeply intertwined with a relic of immense significance—the very spear that pierced Jesus during his Crucifixion. Legend has it that Apostle Jude, also known as Thaddeus, brought this sacred relic to Armenia, and for centuries, it was housed within the monastery’s walls, a silent guardian of faith and history.

Table of Contents

The Proshyans: Masters of Stone and Patrons of Piety

In a whirlwind of creativity and craftsmanship, the Proshians transformed Geghard into a treasure trove of architectural marvels. Over a relatively brief period, they sculpted into existence a series of cave structures that would forever enshrine Geghard’s name in the annals of Armenian architectural excellence. First came the second cave church, a testament to the Proshians’ unwavering faith and their mastery of carving stone into breathtaking forms. Then, the family sepulcher of Zhamatun Papak and Ruzukan emerged from the mountain’s embrace, a silent testament to the enduring bond of family and the Proshians’ reverence for their ancestors.

In a touching tribute to their beloved prince, the Proshians carved a tomb for Prince Prosh Khaghbakian in a chamber reached from the northeast of the gavit. The adjacent chamber bears the arms of the Proshian family, etched into the rock with exquisite detail, including an eagle clutching a lamb in its claws – a symbol of both power and humility.

Katoghiké, The Main Church

Whispers of a bygone era emanate from the stone, with inscriptions dating back to the 1160s. However, the crown jewel, the grand church, rose to its full glory in 1215, championed by the indomitable Zakare and Ivane brothers, famed generals who served Queen Tamar of Georgia in her triumphant reclaiming of Armenian lands from the Turks. The gavit, partly sculpted from the cliff itself, predates even the grand church, established before 1225. A captivating chorus of smaller chapels, painstakingly hewn from the rock itself, arose in the mid-13th century under the patronage of Prince Prosh Khaghbakian, a loyal vassal of the Zakarians and architect of the burgeoning Proshian principality.

The main architectural complex, completed in the 13th century AD, is a testament to the ingenuity and artistry of its time. At the heart of this complex lies the Katoghiké, the main church, a masterpiece of classic Armenian architecture. Its form, an equal-armed cross inscribed within a square, is crowned by a majestic dome, supported by a square base and gracefully linked to the base through vaulting. This harmonious design, reminiscent of the divine balance between heaven and earth, speaks volumes about the architectural prowess of the era. Flanking the Katoghiké are the eastern and western rock-cut churches, their facades sculpted directly into the mountainside.

These structures, adorned with intricate carvings and bathed in the soft glow of natural light, exude an aura of serenity and reverence. Further enriching the tapestry of the monastery’s heritage is the family tomb of the Proshyan princes, a lasting tribute to the legacy of Armenian nobility. Papak’s and Ruzukan’s tomb chapel, with its distinctive architectural features, adds another layer of intrigue to this historic ensemble. Stepping through the southern portal of Katoghike is like stepping into a realm of exquisite artistry, where nature and symbolism intertwine to create a masterpiece of Armenian craftsmanship.

The tympanum, the triangular space above the doorway, is adorned with a delicate tapestry of pomegranates, their plump fruits hanging like jewels from the branches of stylized trees. Intertwining with these symbols of abundance are graceful vines laden with grapes, their leaves intertwining in a harmonious dance. As your eyes travel upwards, you encounter a pair of doves, their heads turned inwards, their presence a gentle reminder of peace and purity. Flanking the arch, these feathered messengers seem to guide you into the sanctuary that lies beyond. Crowning the portal is a powerful carving of a lion, its mighty jaws clamped around the neck of an ox. This symbolic representation of the prince’s power serves as a potent reminder of the unwavering strength and dominion that lie within the walls of Katoghike.

And as you gaze upon the arched top of the arcature that encircles the cupola’s drum, a symphony of intricate reliefs unfolds before you – birds taking flight, human masks frozen in a silent dialogue, animal heads peering out from the stone, rosettes and jars adding a touch of delicate ornamentation. Each element, carefully carved and meticulously placed, contributes to the harmonious tapestry that adorns this architectural gem. Katoghike’s southern facade is more than just an entrance; it is an invitation to enter a realm of artistry, where nature’s bounty intertwines with symbolism, and where the power of the prince is immortalized in stone. It is a testament to the enduring legacy of Armenian craftsmanship, a legacy that continues to inspire and captivate visitors to this sacred site.

St. Astvatsatsin Church

The most impressive structure is the main church, St. Astvatsatsin, whose soaring dome and intricate carvings stand as a masterpiece of Armenian architecture. St. Astvatsatsin Chapel, the Holy Mother of God’s sanctuary, stands as the oldest surviving monument beyond the monastery walls. Its walls, partially hewn from the mountain’s embrace, bear the weight of centuries, adorned with inscriptions that whisper stories from the past. The earliest of these tales date back to 1177 and 1181 AD, echoes of a time when faith and stone intertwined. In the 17th century, as time marched on, residential and economic constructions arose, adding new layers to the monastery’s rich tapestry.

The church’s interior is adorned with frescoes depicting scenes from the Bible and Armenian history, adding a touch of spiritual artistry to the rock-hewn space. Venture deeper into the monastery complex, and you’ll discover a hidden world of caves and grottoes, each adorned with intricate carvings and bas-reliefs. These sacred spaces, once used for worship and meditation, offer a glimpse into the spiritual life of Armenian monks.

The eastern arm of the cross reaches out to embrace the apse, while the rest of the structure stands foursquare against the world. In the corners, two-story chapels tuck themselves away, their barrel-vaulted roofs whispering secrets to the heavens. The interior walls are adorned with a chorus of inscriptions. Outside, the masonry sings a song of precision and grace, a symphony of stone that speaks of devotion and artistry. A gavit, a welcoming hall, serves as a bridge between this architectural gem and the rock-cut church that stands as its silent predecessor.

The Zhamatun

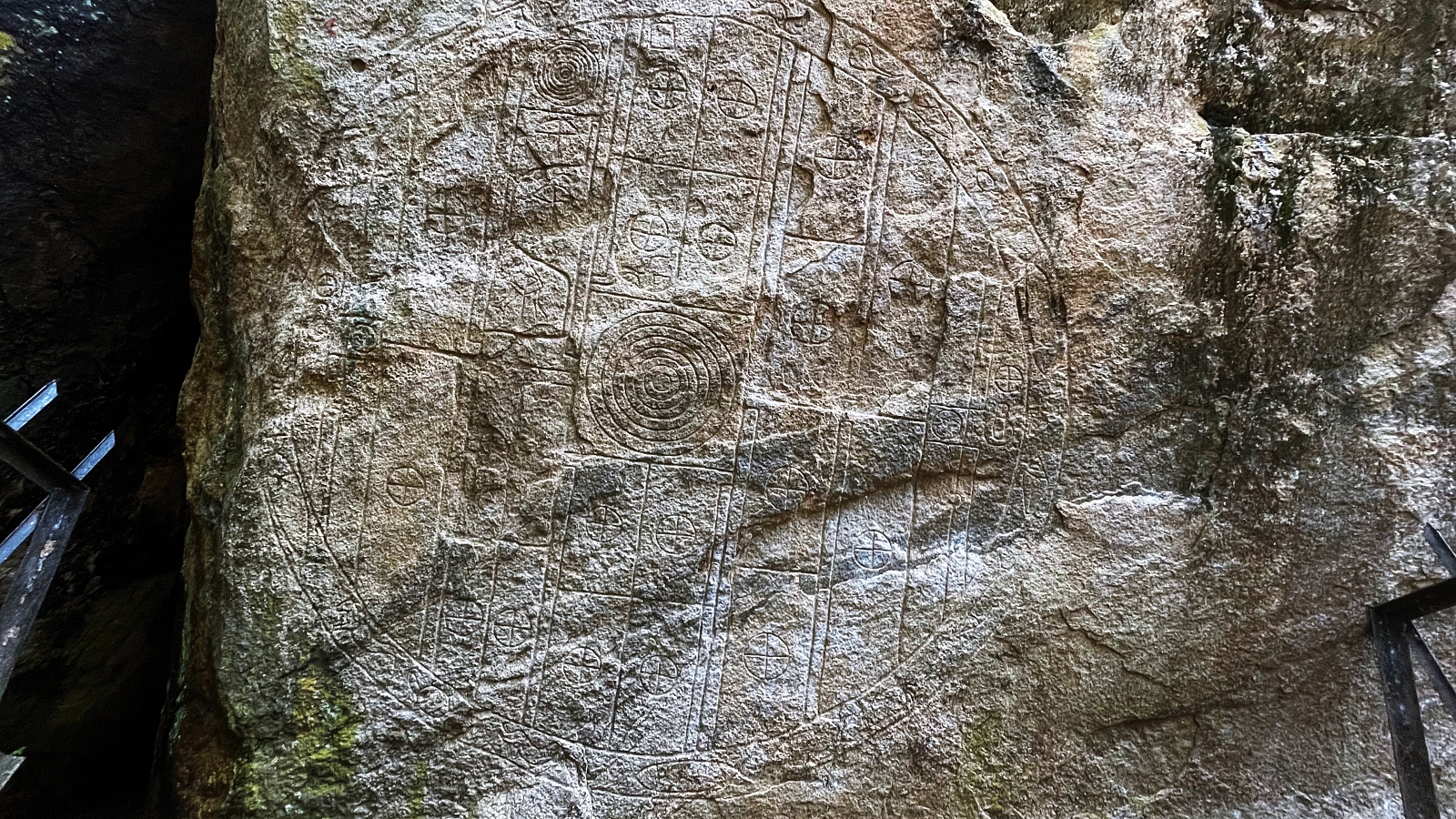

Eastward from the bustling town of Avazan, two architectural gems stand as silent sentinels of the past – the Proshyans’ sepulchre and the second cave church of Astvatsatsin. These magnificent structures, hewn in 1283 by the skilled hands of Galdzak, are accessed through the gavit, a narthex-like chamber that serves as a gateway to these subterranean treasures. Stepping into the zhamatun, a roughly square chamber carved into the rock, one is immediately struck by the deeply cut reliefs adorning the walls. These intricate carvings, a testament to the artistry of their creators, offer a glimpse into the symbolism and beliefs of the Proshians.

Of particular interest is a rather primitive high relief on the northern wall, above the archways. In the centre of this tableau, a ram’s head emerges, its jaws clamped around a chain. This chain, a symbol of both strength and unity, winds its way around the necks of two lions, their heads turned towards the viewer, their expressions conveying both power and vigilance. Instead of the tail tufts that lions typically bear, this depiction features the heads of upward-looking dragons – symbolic images that trace their roots to ancient pagan beliefs. These creatures, often associated with wisdom and guardianship, add an air of mystique to the scene.

Between the lions and nestled beneath the chain, an eagle with half-spread wings proudly displays its catch – a lamb firmly clutched in its claws. This potent symbol, often associated with royalty and power, is believed to represent the coat-of-arms of the Proshian Princes, a lineage that played a pivotal role in shaping Armenia’s rich history. As one contemplates these intricate carvings, it is easy to imagine the stories they could tell, tales of bravery, faith, and enduring power. The Proshyans’ sepulchre and the second cave church of Astvatsatsin, hidden within the embrace of the earth, stand as enduring testaments to a bygone era, whispering secrets of the past to those who take the time to listen.

The Vestry, Gavit

Within the serene embrace of Geghard Monastery, a cave church wall bears silent witness to the passage of time, its weathered surface adorned with the indelible etchings of engraved crosses. These sacred symbols, etched with reverence and devotion, stand as poignant reminders of the unwavering faith that has echoed through the centuries within these hallowed halls. Westward from the monastery’s main temple, a remarkable rock-attached vestry, known as the gavit, graces the landscape. Constructed between 1215 and 1225, this architectural gem stands as a testament to the ingenuity and artistry of its creators.

Four massive, free-standing columns rise from the heart of the gavit, their sturdy forms supporting a roof of stone that gently yields to the sky, allowing a cascade of natural light to illuminate the space below. The peripheral spaces, cleverly arranged around the central columns, provide shelter and tranquillity, while the central area is crowned by a mesmerizing dome adorned with stalactites, a masterpiece of Armenian architectural technique. This magnificent gavit served as a hub of activity, a place where knowledge was imparted, meetings were conducted, and pilgrims and visitors were warmly welcomed. The western portal, a departure from the architectural norms of its time, features van-shaped door bands delicately adorned with a fine floral pattern.

The tympanum, the triangular space above the doorway, is home to an exquisite display of large flowers, their petals meticulously carved in various shapes, interlaced with branches and oblong leaves. This intricate artistry, born from the hands of skilled artisans, transforms the gavit’s entrance into a portal of beauty and symbolism. Within the gavit’s walls, faith and art intertwine, creating a sanctuary where spiritual reflection and artistic appreciation converge. The engraved crosses on the cave church wall whisper tales of unwavering devotion, while the architectural splendour of the gavit stands as a testament to human ingenuity and artistry. In this sacred space, the echoes of the past harmonize with the beauty of the present, creating a timeless symphony of faith and creativity.

Upper Jhamatun

Hidden within the heart of Geghard Monastery’s cliffs, a second jhamatun, known as Papak and Ruzukana’s Zhamatun, stands as a silent testament to the enduring legacy of the Proshian princes. Hewn in 1288 on a level above the Proshians’ burial-vault, this architectural gem is accessed via an external staircase, its entrance nestled near the door to the gavit. Within its walls lie the tombs of the princes Merik and Grigor, their names forever etched in the annals of Armenian history. Though other tombs once graced this chamber, time has taken its toll, their presence now known only through the whispers of the past. An inscription, proudly displayed upon the stone, reveals the jhamatun’s completion in 1288.

Along the southern side of the corridor leading to this sanctuary, a multitude of crosses are carved into the rock, their presence a silent benediction upon all who enter. Atop a cupola, a delicate opening allows a gentle stream of light to illuminate the space below, creating an ambience of ethereal tranquillity. In the back right corner of the jhamatun, a strategically positioned hole offers a glimpse into the tomb situated below, a reminder of the enduring bond between the living and the departed. The acoustics within this chamber are extraordinary, each sound resonating with an almost otherworldly quality as if the walls themselves are whispering tales of the past.

Chapel of S. Grigor

A hundred meters away from the entrance to Geghard Monastery, a sentinel of faith stands tall – the Chapel of S. Gregory the Illuminator, formerly known as the Chapel of the Mother of God – St Astvatzatzin. Built before 1177, this architectural gem blends seamlessly with the natural contours of the rock face, its very form shaped by the cave that once existed within its embrace. Rectangular in plan, the chapel features a horseshoe-shaped apse, a testament to the harmonious fusion of architectural artistry and the organic beauty of the rock from which it was carved. From the east and northeast, passages and annexes, intricately hewn at various levels, extend outwards, creating a labyrinth of sacred spaces that echo the tranquillity of the surrounding cliffs.

Traces of plaster, adorned with remnants of dark frescoes, hint at the vibrant murals that once adorned the chapel’s walls, their faded colours whispering tales of a bygone era. Khachkars, intricately carved stone crosses adorned with exquisite ornamentation, grace the exterior walls and adjacent rock surfaces, their silent presence adding a touch of spirituality to the landscape. The dim light filtering through the narrow openings cast an ethereal glow upon the stone surfaces, creating an atmosphere of hushed reverence. The chapel’s acoustics, honed by the natural contours of the rock, amplify every sound, transforming each whisper into a sacred echo.

Khachkars: Armenian Cross-Stones

Khachkars stand as enigmatic sentinels of faith, their intricate carvings silently narrating tales of devotion, commemoration, and the delicate balance between the secular and the divine. These carved steles, reaching an impressive 1.5 meters (5 feet) in height, are more than just memorial stones; they are embodiments of Armenian spirituality, each stroke of the chisel breathing life into stone, transforming it into a conduit for divine communication. Khachkars are meticulously carved from local stone, their surfaces adorned with a mesmerizing array of patterns.

At the heart of each Khachkar lies a decorative cross, a symbol of unwavering faith, resting gracefully upon a sun or wheel of eternity, representing the cyclical nature of life. These central motifs are often accompanied by a symphony of carvings, depicting saints, animals, and plants, each element imbued with deeper meaning and symbolism. Once a Khachkar is completed, it undergoes a ritual of blessing, imbuing the stone with the power to aid in the salvation of the soul.

At the Monastery of Geghard, a veritable sanctuary of Khachkars, these stone sentinels stand sentinel, their intricate carvings whispering stories of devotion and remembrance. More than 20 structures, each carved directly into the mountainside, grace the monastery grounds, ranging in size and complexity from churches to tombs, vestries to chapels. Each stroke of the chisel has left its mark, breathing life into the stone, and transforming it into a conduit for spiritual expression.

These stone masterpieces, adorned with floral and geometrical motifs, grace both the exterior and interior walls, transforming the monastery into a living tapestry of artistry and faith. Just as the carvings throughout the Geghard complex reflect a harmonious blend of natural and human artistry, so too do the Khachkars embody this unique fusion. These Khachkars are not mere adornments; they are integral elements of the Geghard Monastery’s identity, imbuing the sacred space with an aura of serenity and reverence. As visitors wander through the complex, their eyes are drawn to these stone masterpieces, their intricate carvings sparking reflection and igniting the imagination.

A Sacred Spring

As you wander through the monastery’s labyrinthine passages, the sound of trickling water fills the air. A sacred spring, believed to possess healing powers, flows through the complex, adding a touch of mysticism to the ancient atmosphere. The Monastery of Geghard is not merely a collection of architectural marvels; it is a living embodiment of Armenian heritage and spirituality. Its unique blend of rock carving, intricate artistry, and spiritual significance makes it a truly remarkable destination, a place where history and nature intertwine in a harmonious masterpiece.

Among the monastery’s cherished possessions was the Spear of Destiny, the very weapon that pierced Christ’s side on the cross. Legend has it that Apostle Thaddeus brought this relic to the monastery, earning it its name, Geghardavank, the Monastery of the Spear. For five centuries, the spear resided within the monastery walls, a silent witness to the ebb and flow of time. In the 12th century, relics of the Apostles Andrew and John joined the Spear of Destiny, adding to the monastery’s aura of sanctity. Pious visitors, their hearts filled with devotion, flocked to Geghardavank, offering generous gifts of land, wealth, and manuscripts, each a testament to their unwavering faith.

Within the monastery complex, churches emerge from the cliff rocks like architectural apparitions. Some are entirely carved into the stone, others resemble caves, while others are elaborate structures with intricate walls and chambers deep within the cliff’s embrace. This harmonious blend of architecture, along with numerous engraved and free-standing khachkars, creates a visual symphony that is uniquely Geghardavank. This architectural marvel stands as one of Armenia’s most popular tourist destinations, drawing visitors from far and wide to admire its harmonious blend of nature and human artistry.

Many visitors to Geghardavank also choose to venture further down the Azat River to explore the nearby pagan Temple of Garni. This ancient temple, with its distinctive Greco-Roman architecture, stands as a testament to Armenia’s rich and diverse history. The proximity of these two sites has made them an inseparable pair, often referred to as Garni-Geghard, a must-visit destination for anyone seeking to delve into the depths of Armenian culture and heritage.

Visiting Garni and Geghardavank in one trip is a common practice, allowing visitors to experience the full spectrum of Armenian history, from the ancient pagan era to the Christian Middle Ages. The combination of these two sites offers a unique glimpse into the cultural tapestry of Armenia, where ancient traditions and beliefs coexist in harmonious coexistence.