Aapravasi Ghat: A Dent of Indian History

“The Aapravasi Ghat is where the ancestors of almost 70% of the Mauritian population arrived on the island from 1849 to 1920s. After Mauritius became independent in 1968, the Aapravasi Ghat was gradually recognised as a major landmark for Mauritian history,” are the words printed above Indira Gandhi’s photo who visited the site in 1978.

A crimson signboard with white alphabets marks the entrance of Aapravasi Ghat in Mauritius. Bricked walls on both sides appear a few steps down. These are from the original site, as it was between 1834 and 1920 when it held nearly half a million indentured slaves transported from India to work in Mauritius’ sugar fields, or to be relocated to Reunion Island, Australia, southern and eastern Africa, or the Caribbean. A circular signboard bears a rectangular cue with the etched footprints of a child marking the landing point of indentured immigrants out in the open grounds.

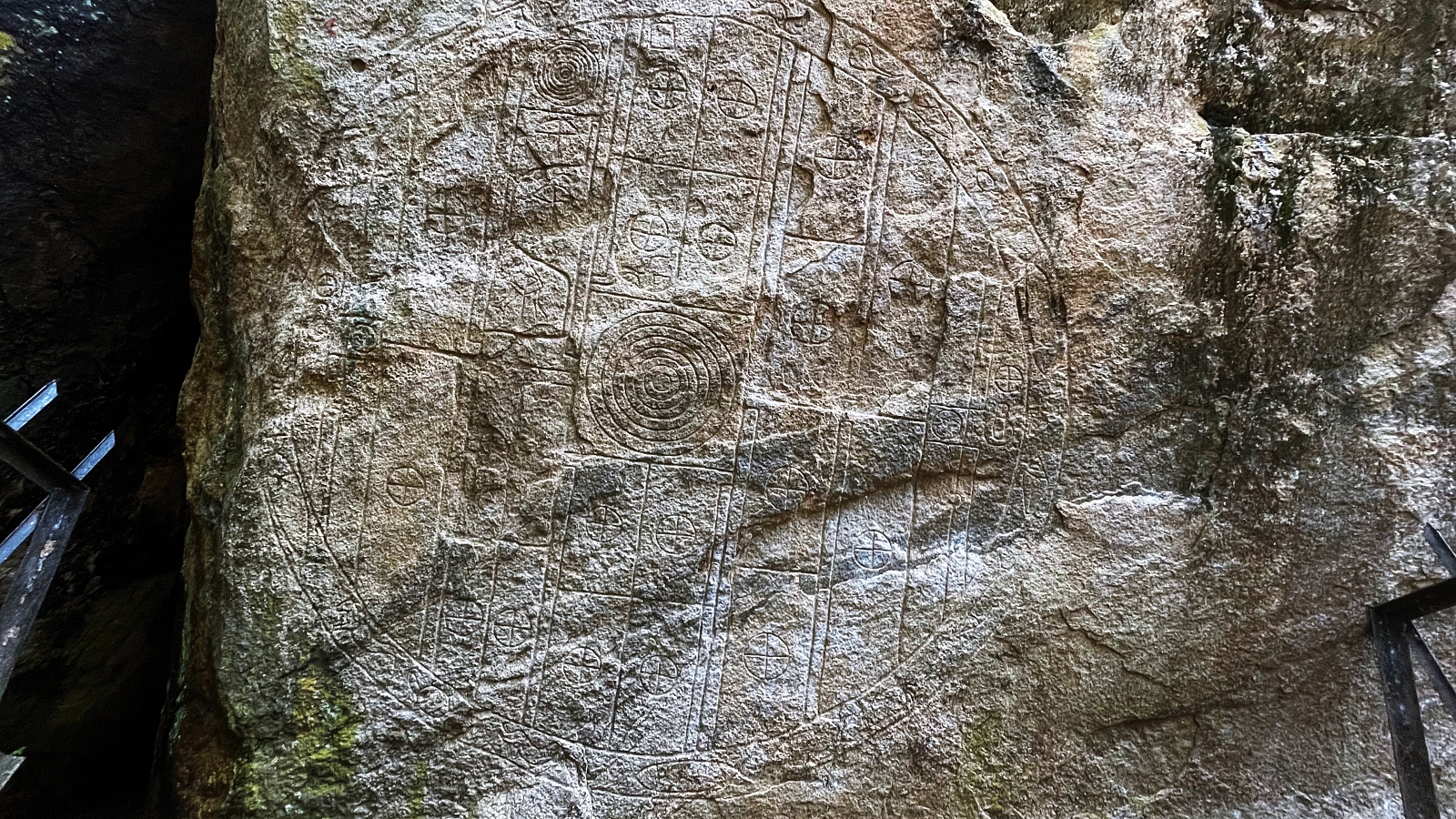

The museum, on the other hand, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a modern, air-conditioned institution that houses the relics of a dreadful history. Aapravasi Ghat is near the Mauritius Postal Museum and faces the harbour. If you’re facing the port; the museum is on the right, and the building on the left is maybe one of the original structures. Two circular figures zigzag through a stone track as they rest on the ceiling. When you enter the building, though, everything turns flat. Inside the museum, I met my guide at the glass stand.

Pelted stones from the original site adorn the bottom of the piece, and my guide was quick to point out the rope tied cylindrical aluminium containers that adorn the top. Each container has a name marked, as these are some of the personal items of the immigrants who stayed at the facility at the time. As the tour begins, a sense of despondency sets in. What if I was one of them? is a constant thought that runs through your mind. A child earned 2.50 cents a day, a woman 3 cents, and a man 5 cents per day, but it required all of God’s grace, miracles, and compassion to put an end to slavery.

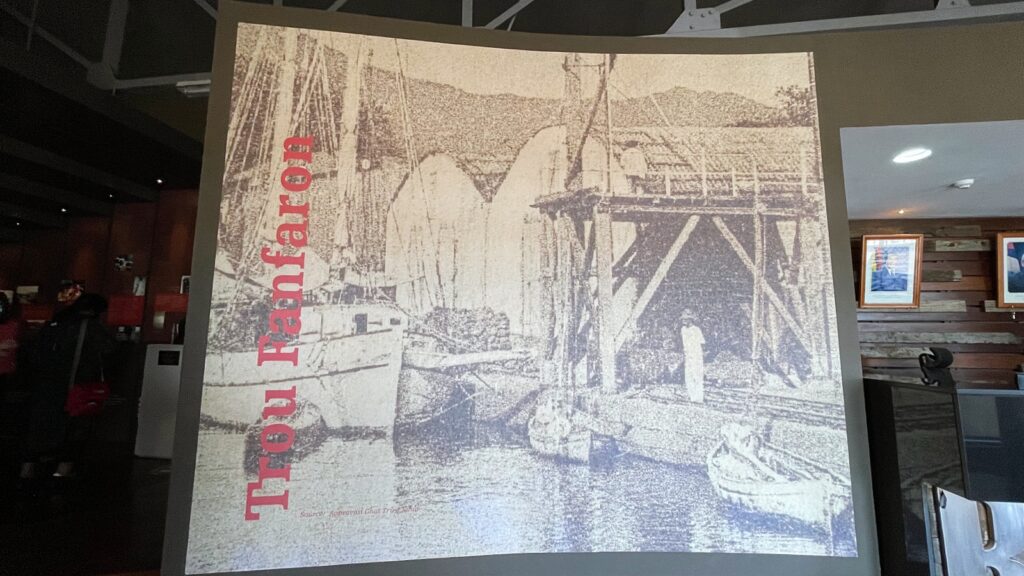

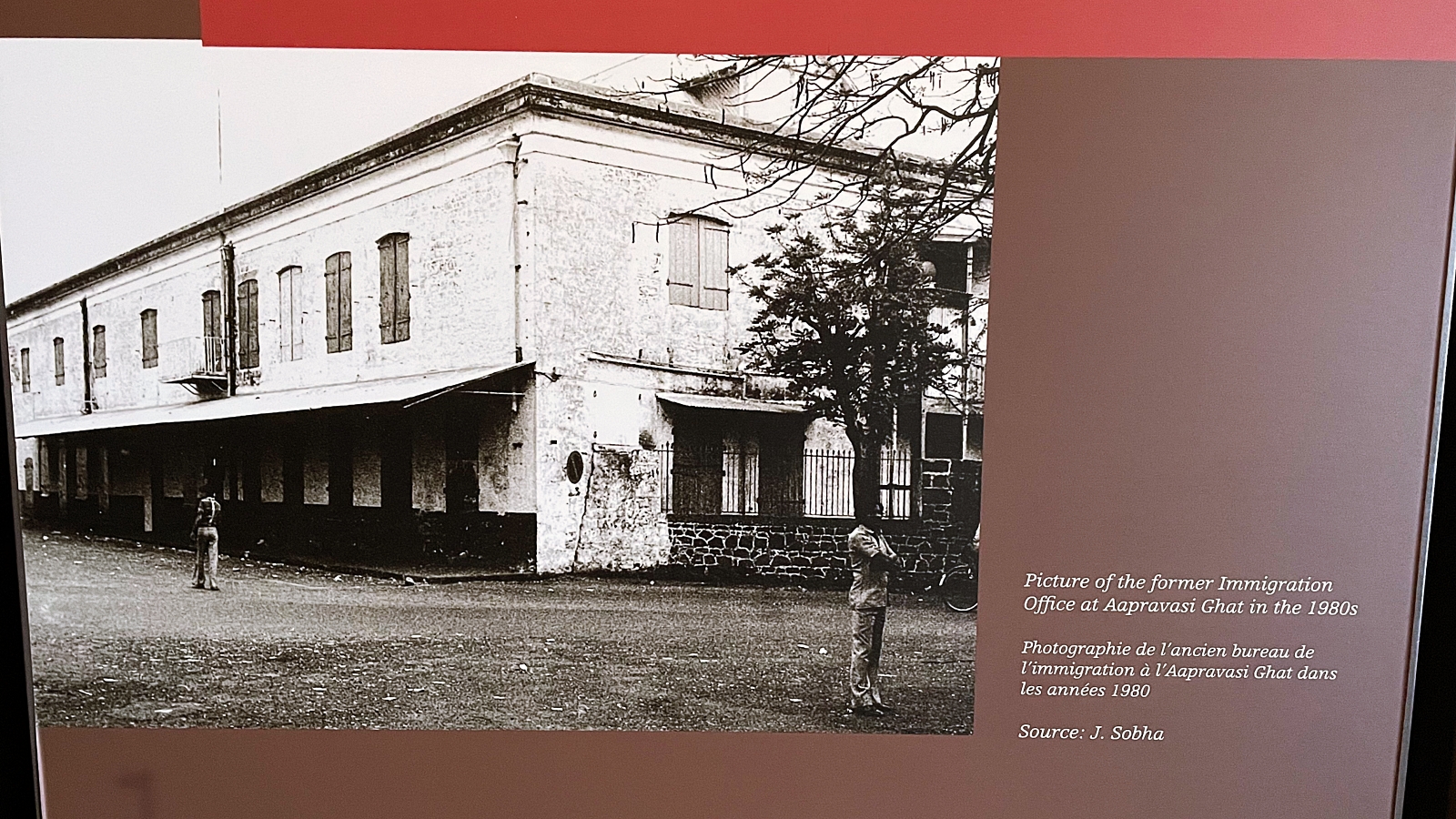

Reminiscences of the slaves’ and masters’ tools, ceramics, and other personal belongings unfolded one after the other as we moved from room to room. The first billboard I came upon was Trou Fanfaron. Nicolas Huet, a coal merchant from Saint-Malo, France, was known as Fanfaron, and the Bay of Trou Fanfaron near Port Louis, where the World Heritage Site of Aapravasi Ghat is located, might have been named after him. The signage leads to another that foreshadows the evolution of this site over time.

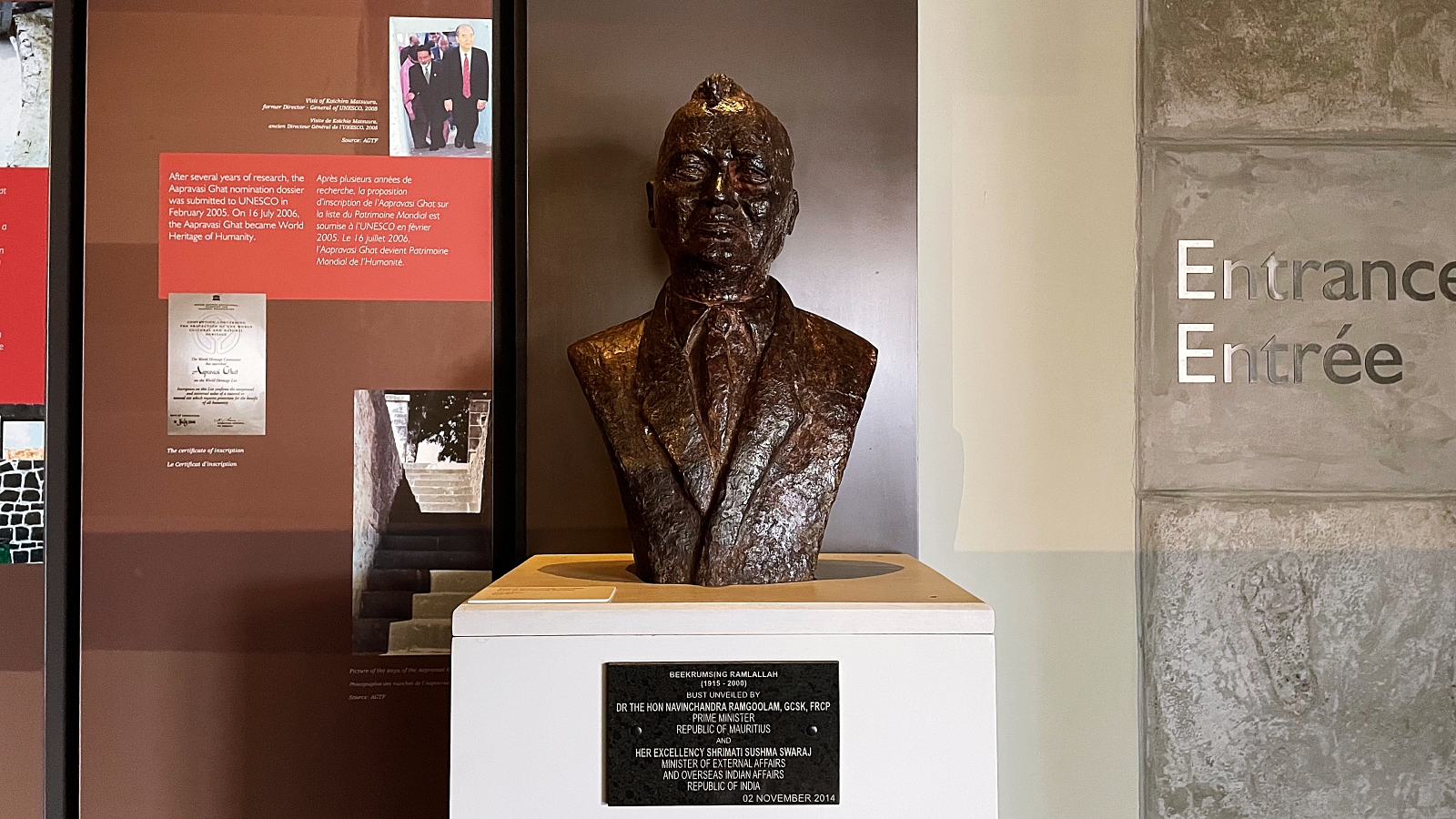

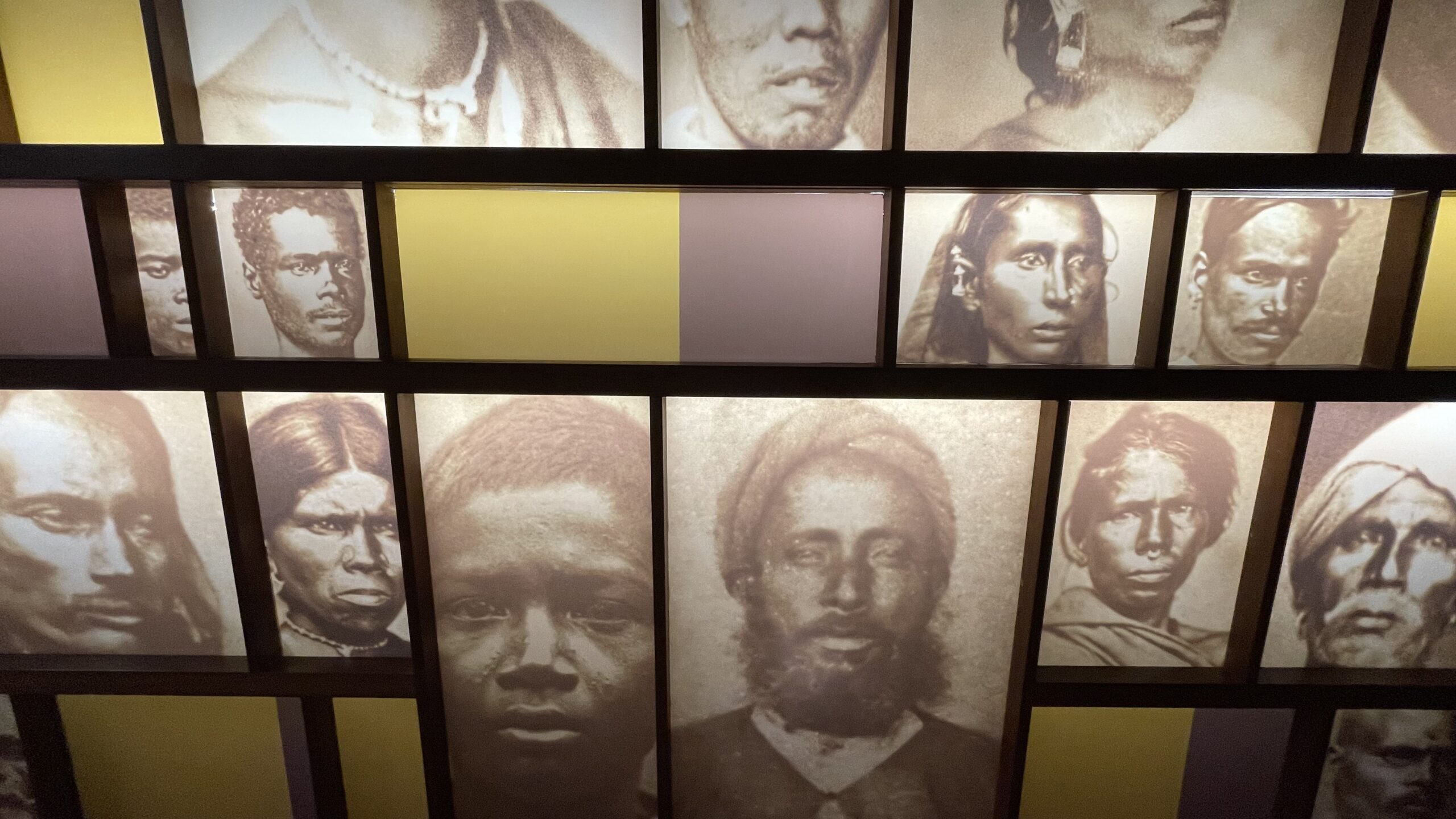

This wall of fame is monopolised by old black and white pictures. A stone statue of Beekrumsingh Ramlallah rests right next to the signage. Beekrumsingh Ramlallah organised the first public ceremony at the Coolie Ghat in 1978 to honour the memories of the indentured labourers who had landed there.

The Coolie Ghat was appointed as a national monument in April 1987. Because of the negative connotation linked to the nickname Coolie, the Coolie Ghat was renamed, Aapravsi Ghat in 1989. In Hindi, Aapravasi Ghat means “immigrant landing place.” Today, this museum serves as a tribute to humanity’s indentured immigrants.

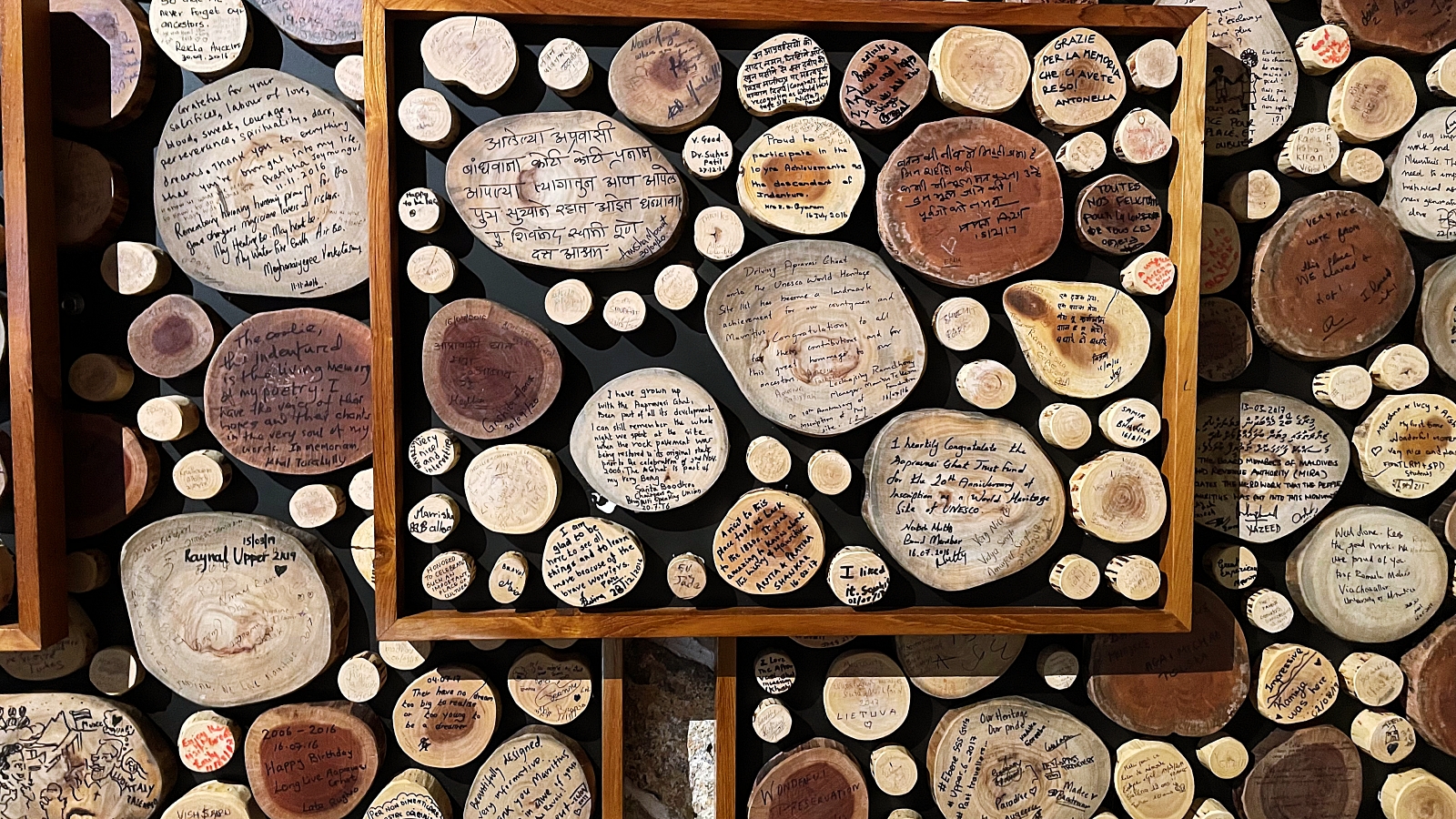

The date of November 2, 2001, was declared a public holiday in honour of the indentured labourers in July 2001. “I have grown up with the Aapravasi Ghat, been part of all of its development. I can still remember the whole night we spent at the site when the rock pavement was being restored to its original state prior to the celebration of 2nd November 2006. The AGhat is part of my very being,” reads a wooden board signed by Sanita Boodhoo, chairperson of Bhojpuri speaking union.

You’ll get goosebumps reading notes from cadres of similar people. If there’s anything left to feel, the life-size images of immigrants will break your heart. Take a trip with the guide to see the items on display, which include glasses, bowls, saucers, rice liquor cups, wine bottle bases, pipe fragments, plate fragments, lid and soup tureen, ploughing tools, a cartwheel and the oil-burning lamps, among other things.

The trip to AGhat culminates with a visit to the closed cells and washrooms where the immigrants showered. Don’t be deceived by the sumptuous grandeur of these compartmentalised chambers; as they were meant to be occupied by multiple individuals at a time. Women were only allowed to use the one with the stairs. A huge garden facing the city is attached to this space on the first level. I grabbed a couple of photographs of the port while climbing down because this is where you get the finest perspective of it.

Trou Fanfaron, the location of the building complex, was the landing site for the French East India Company when it acquired possession of Mauritius in 1721. During the early stages of settlement, slaves were hauled from Africa, India, and Madagascar to build defensive walls and a hospital. Slave labour was used to establish sugar plantations on the island of Mauritius during the mid-eighteenth century. Mauritius came under British sovereignty in 1810 during the Napoleonic Wars, as reaffirmed by the Treaty of Paris, at a time when the British Empire was increasing its influence in the Indian Ocean region.

Beginning mid-18th century, British economic interest led to an expansion in sugar production, which became the most essential commodity in European trade, resulting in the development of infrastructure for Port Louis as a free port. Overall, a visit to Aapravasi Ghat helped me comprehend Mauritian locals’ psyche, and while it’s difficult to enjoy sugar plantations because of their history, Mauritian sugar did, in an ironic turn of events, play a significant role in sweetening the lives of the islanders. Visit this prominent Mauritius monument to have a better understanding of the island.

With everything that is going on in the world right now, let us turn our attention to the objects of reform and justice, the ideas that have shaped the world for the better. Let us purge our minds of hatred and mend the dent the way Mauritius did.